Grandpa Karl and cousin Laura, a story of enduring inspiration

If, uprooting from its heart the vice which dominates it and degrades

its nature, the working class were to arise in its terrible strength,

not to demand the Rights of Man, which are but the rights of capitalist

exploitation, not to demand the Right to Work which is but the right to

misery, but to forge a brazen law forbidding any man to work more than

three hours a day, the earth, the old earth, trembling with joy would

feel a new universe leaping within her. But how should we ask a

proletariat corrupted by capitalist ethics, to take a manly resolution

...

Paul Lafargue,

The Right to be Lazy, 1883.

Paul Lafargue,

The Right to be Lazy, 1883.

I have met Karl Marx at the age of 17, Pablo Picasso

at 18 and James Joyce in my twenties. Far away have been pushed these

beautiful

student days but I remember very clearly the strange intimacy I felt to

these three

mythical figures. Getting to know them more and more closely meant to me

getting accustomed to an unexpected and long-desired kind of

inexplicable in plain words

''pleasure'': La joie de vivre. Or, better: La jouissance de vivre. That was the exact feeling. Bliss.

Seen from a more realistic, more personal aspect one has to admit that meeting with them probably suggested a substitute of physical grandfathers I had never a chance to meet in reality. As I came to realize very early, these three figures, coming as they were from another world still unmapped to me, became gradually soul relatives bringing along as a gift to their grandchild all the wisdom of the world and a bit of fancy – and, since they were very intelligent people they could manifest a certain spiritual affection towards me, understanding, as they did, better than anything and anyone else my desperate need to increase my narrow percentage of freedom in this oppressive society.

Marx made my young heart beat with excitement each time his obsessive Belief in the Utopian Dream crossed my mind: From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs! And then Picasso –with his also obsessive, almost childish in its innocence, dexterity to recreate the world out of every possible visual material– inspired tremendously my need to see palpable reality through my improvising imaginary vision. Last but not least Joyce, in a similar way to Picasso, (e.g.: with his equally obsessive and childish in its innocence, dexterity to recreate the world, out of every possible linguistic material), unleashed freedom to the wings of my writing ambitions. All of them had something in common: they kept believing and passionately demanding in life and art a radically different world.

And then, at a later age, I made the acquaintance of my dearest cousins Paul Lafargue and Laura Marx as well as that of my eldest brother: Marcel Duchamp. He made his playful, yet somewhat dramatic, entrance into my world in my thirties. I hold the same ideas on art as him but I have never been able to apply them in my everyday reality, I have never had the courage or the means (may be it is the same) to be the activist of his stature. Greece is such a sterile country, a waste land where you can't be brave because nobody expects you to be one.

Seen from a more realistic, more personal aspect one has to admit that meeting with them probably suggested a substitute of physical grandfathers I had never a chance to meet in reality. As I came to realize very early, these three figures, coming as they were from another world still unmapped to me, became gradually soul relatives bringing along as a gift to their grandchild all the wisdom of the world and a bit of fancy – and, since they were very intelligent people they could manifest a certain spiritual affection towards me, understanding, as they did, better than anything and anyone else my desperate need to increase my narrow percentage of freedom in this oppressive society.

Marx made my young heart beat with excitement each time his obsessive Belief in the Utopian Dream crossed my mind: From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs! And then Picasso –with his also obsessive, almost childish in its innocence, dexterity to recreate the world out of every possible visual material– inspired tremendously my need to see palpable reality through my improvising imaginary vision. Last but not least Joyce, in a similar way to Picasso, (e.g.: with his equally obsessive and childish in its innocence, dexterity to recreate the world, out of every possible linguistic material), unleashed freedom to the wings of my writing ambitions. All of them had something in common: they kept believing and passionately demanding in life and art a radically different world.

And then, at a later age, I made the acquaintance of my dearest cousins Paul Lafargue and Laura Marx as well as that of my eldest brother: Marcel Duchamp. He made his playful, yet somewhat dramatic, entrance into my world in my thirties. I hold the same ideas on art as him but I have never been able to apply them in my everyday reality, I have never had the courage or the means (may be it is the same) to be the activist of his stature. Greece is such a sterile country, a waste land where you can't be brave because nobody expects you to be one.

|

Grandfather Karl

I owe to marxism whatever ethical values I still consider most important for a decent, human life. The humanist perspective of marxist theory reflected my youth's demand for social and cultural change. Marx helped me to inquire about the world in a daring, not negotiable way, pushing my thought to unexplored paths beyond the conservative bourgeois interpretations of my academic curriculum. One of the most important things I learned from him early enough was the critical importance of the relationship between Structure and Superstructure – the marxist analysis of the dialectic process between the two helped me conceive very clearly the wrong direction of the then dominant Left 's position on this issue (principally in USSR); a direction which was solidly established in Stalin's era and considered dogmatically this process as a one-way road from Structure to Superstructure thus minimizing the impact of the second to the economic foundation of society and, what is more, to the foundation of a socialist society. I believe that marxist theory especially today, after it has been richly fertilized with the disappointing experience of the ex-communist regimes while the world has turned into global, it still remains a super food for thought whenever one is obliged to face in his everyday life the ancient questions concerning social Injustice and authoritarian Power. |

Grandfather Pablo

Generosity. Generosity in Art is a very rare thing. Only the Great Masters offer their talent with generosity. To be generous in Art means to be like Picasso: he offered to the world an abundant visual medium to cure every possible artistic desire, to respond to every possible aspect of the humanist ideal – without going down to whatsoever canon or authority or principle or tradition. He recreated the world visually. He liberated our aesthetic perception of the world in more than one ways. However stingy he has been as far as money are concerned he proved himself generous to art. Picasso's generosity serves as a royal road to self-liberation. His road, his way of seeing, guided mine since my early youth. These postmodern times we live in, Picasso's example should still be a beacon to young people in quest of personal freedom. Those who are intelligent enough to turn their back to the piles of postmodern debris that besiege the so-called museums of contemporary art should be also intelligent enough to re-read Picasso today. To this day he remains a generous teacher. |

|

Grandfather James

The world was lost from my sight the moment I had read the first page. Of Ulysses. As I said before, that happened at the age of 20. It was something like a nervous breakdown, my soul was cut in parts, I lost myself, who I was, which way would I go from now on. And I went on. And on. I practically have never stopped reading Ulysses, Joyce. I still keep in the Joyce shelves of my library the old standard edition of 1968 and yes, I will never quit Joyce, yes. Picasso is all that painting is. Joyce is all that literature is. Going through Picasso's œuvre you can study all the history of art. Going through Joyce' s œuvre you can study all literature from Homer and the Bible to the present day. I have learned literature with my grandfather Joyce as I did for German literature with his follower, Herman Broch. But, please, no malicious misunderstanding here: I don't trust those who write ''à la manière de''. I have to say I never committed that stupid crime. And no critic has ever said anything of the kind as regards my work. But then Joyce is a perfect measure for any writer. A comparison measure to judge a writer's improvement, his blunders, his stupidities, his artistic deeds. Because Joyce is like Shakespeare, Homer, Dante, or the Greek tragic poets: He is the absolute School of literature, all the grades from bottom to top: from the elementary to the post-graduate. A lot of people are not aware of this fact. I have been aware in my time, and I feel very lucky for that. ----------------------------------------- Follow my work on Joyce. |

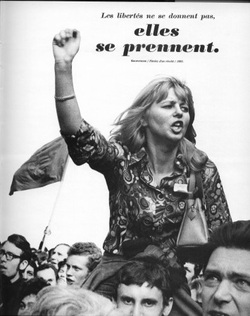

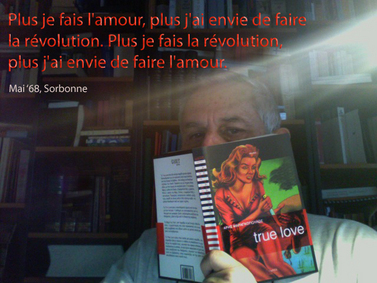

Cousins Paul and Laura

I met Paul Lafargue at the age of 26. When I read for the first time Le Droit à la Paresse (1883, The Right to be Lazy) I suddenly felt that both the Communist Manifesto and the Contrat Social (by Jean-Jacques Rousseau) faded back to their glorious past. It is worth mentioning here that the only biography I have ever read in full (I get easily bored of biographies – of course Joyce' s is an exception…) is that of Lafargue and Laura Marx. These two eternal lovers and revolutionaries, who have lived their difficult life under the dark shadow of the great father and father-in-law, have on many occasions disturbed my sleep. I have always felt that I knew them since time immemorial. (I believe readers of my novels understand that affinity. But may be this is a wishful thinking.) To conclude with: if up to here I made it understood that Marx, Joyce and Picasso have been my beloved grandfathers be it also understood that Paul and Laura have been my dearest cousins: we are always on the alert, ready to play once more, once and for all, the Commune drama, so that one day, not too far from now, we may share the possibility of committing suicide together… |

And there' s a brother to me…

Marcel Duchamp has always been a dear brother to me. An eldest brother, whom I could trust, who could inspire me beyond the monumental borders of grandfathers. Living life as a work of art, showing indifference to the demands of artistic fame and commercialism, Marcel responded to my deeper dreams. I live as Marcel – though I am not Marcel, I am not that artist, that thinker, that wise figure, that chess player, probably even, that lover. Every day of my social life I let loose the curtain of conformity and try to save behind it the pretext of a life led in beauty and truth. But in most times the only thing I gain after such austerity and pain is despair. You must be Marcel to live like Marcel: "I like living, breathing, better than working. I don’t think that the work I’ve done can have any social importance whatsoever in the future. Therefore, if you wish, my art would be that of living: each second, each breath is a work which is inscribed nowhere, which is neither visual nor cerebral. It’s a sort of constant euphoria."*

In my opinion Marcel Duchamp ought to be very happy with the The Right to be Lazy. And Joyce, who has been the alter ego of Picasso in writing, would be very happy with both authors. All these people constitute by and large my real family.

________________

*In: Pierre Cabanne: Entretiens avec Marcel Duchamp. Paris: Pierre Belfond, 1967.

[Eng. trans. by Ron Padgett: Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp. New York: Da Capo Press, 1987, p. 72.]

Marcel Duchamp has always been a dear brother to me. An eldest brother, whom I could trust, who could inspire me beyond the monumental borders of grandfathers. Living life as a work of art, showing indifference to the demands of artistic fame and commercialism, Marcel responded to my deeper dreams. I live as Marcel – though I am not Marcel, I am not that artist, that thinker, that wise figure, that chess player, probably even, that lover. Every day of my social life I let loose the curtain of conformity and try to save behind it the pretext of a life led in beauty and truth. But in most times the only thing I gain after such austerity and pain is despair. You must be Marcel to live like Marcel: "I like living, breathing, better than working. I don’t think that the work I’ve done can have any social importance whatsoever in the future. Therefore, if you wish, my art would be that of living: each second, each breath is a work which is inscribed nowhere, which is neither visual nor cerebral. It’s a sort of constant euphoria."*

In my opinion Marcel Duchamp ought to be very happy with the The Right to be Lazy. And Joyce, who has been the alter ego of Picasso in writing, would be very happy with both authors. All these people constitute by and large my real family.

________________

*In: Pierre Cabanne: Entretiens avec Marcel Duchamp. Paris: Pierre Belfond, 1967.

[Eng. trans. by Ron Padgett: Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp. New York: Da Capo Press, 1987, p. 72.]

Fear not them that sell the body but have not power to buy the soul.

James Joyce,

Ulysses, 16th episode, 1922.

O Laziness, mother of the arts and noble virtues, be thou the balm of human anguish!

Paul Lafargue,

The Right to be Lazy, 1883.

James Joyce,

Ulysses, 16th episode, 1922.

O Laziness, mother of the arts and noble virtues, be thou the balm of human anguish!

Paul Lafargue,

The Right to be Lazy, 1883.