How it all started and how it went on and on and on…

At the age of twenty, my first attempt to write. 1968. A theatrical play it was or something of the kind. Back then I was very young, very innocent, very passionate for love and beauty, very. And the play: very Ionesko like. I still remember the title: Achilles. But then in Greece creators had to limit themselves within the arid landscape of a dictatorship so as soon as I could I fled with a lot of expectations to Europe, Paris. I had in mind to study painting and photography at the École des Beaux Arts. It is true that at the time I felt more like a visual artist than anything else. I remember I used to carry along, wherever I went, from coffee shops to political meetings, a huge pad of drawing paper and, as if I was living in the times of Baudelaire, I kept drawing, making sketches not of the surrounding reality but, again, abstract sketches of imaginary concepts that tormented my young revolting heart!

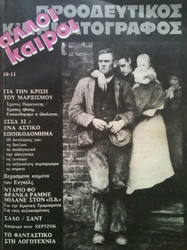

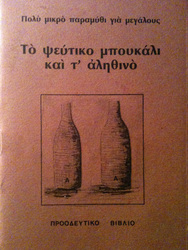

When back to Greece after the fall of the junta I started to write more conscientiously. 1979. My first published attempt was a poem-like booklet issued by the Progressive Cinema (Προοδευτικός Κινηματογράφος), a quarterly magazine on politics, culture and cinema published by a small group of leftist intellectuals (of which I was an active member at the time). Real bottle and Fake bottle (To ψεύτικο μπουκάλι και τ' αληθινό) was the title of that tiny work which also included some crude sketches – the kind I used to draw in Paris.

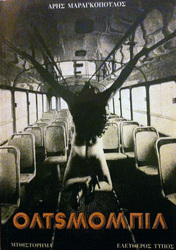

FIRST BOOK: Oldsmobile, a novel

Three years later, in 1982, I published my real first book which as a title bore the brand name of a well-known American car: Oldsmobile. It had nothing to do though, with the Americas. The theme of the American car served simply as a leitmotiv of cultural imperialism. Nobody wanted to publish it. Both the content and the language were a bit provocative for the period and I was too proud to beg the petty, provincial intelligentsia, that held the wheel of the respected publishing houses, to read more carefully my text. So I proposed the book to a small house that produced mostly political texts of anarchic content and, until then, had not published any demanding literature. In the course of time that otherwise instinctive move has been proved very intelligent: a lot of young people who shared my libertarian ideas were also the fans / clients of this house and so they had been reading and discussing extensively my novel.

SECOND AND THIRD BOOK: Short stories

So at the beginning of the eighties I started to feel all the more confident about my writing vocation; some day, in the near future, I would be a writer. Psycho-brothel (1983) and This is no cinema, baby (1985), two short story collections (with some poems loosely incorporated into the narrative of both) had a certain impact to the then anarchist youth movement in Greece, and to such an extent that the latter title became a familiar slogan that was posted on every wall in the Exarcheia district, the students' "Rive gauche" in Athens. I was reading the beatniks at the time. And some of the classic Greek writers, pre-modernists of the 19th century (Papadiamantis, Bizyinos, Roides, Mitsakis). And Joyce, of course, that goes without saying. Plus Bukowski.

These first three books constitute, in their peculiar way, a trilogy of experiments in content and style – in fact more in style, content didn't bother me much because, one way or another, it was meant to be committed to my socialist utopian positions. Style, narrative form, that was what I worked more intensely upon because I understood literature primarily as an art form. And I still do. (More about this trilogy, which I loosely call The A.M.'s 80's trilogy, you may read here.)

When back to Greece after the fall of the junta I started to write more conscientiously. 1979. My first published attempt was a poem-like booklet issued by the Progressive Cinema (Προοδευτικός Κινηματογράφος), a quarterly magazine on politics, culture and cinema published by a small group of leftist intellectuals (of which I was an active member at the time). Real bottle and Fake bottle (To ψεύτικο μπουκάλι και τ' αληθινό) was the title of that tiny work which also included some crude sketches – the kind I used to draw in Paris.

FIRST BOOK: Oldsmobile, a novel

Three years later, in 1982, I published my real first book which as a title bore the brand name of a well-known American car: Oldsmobile. It had nothing to do though, with the Americas. The theme of the American car served simply as a leitmotiv of cultural imperialism. Nobody wanted to publish it. Both the content and the language were a bit provocative for the period and I was too proud to beg the petty, provincial intelligentsia, that held the wheel of the respected publishing houses, to read more carefully my text. So I proposed the book to a small house that produced mostly political texts of anarchic content and, until then, had not published any demanding literature. In the course of time that otherwise instinctive move has been proved very intelligent: a lot of young people who shared my libertarian ideas were also the fans / clients of this house and so they had been reading and discussing extensively my novel.

SECOND AND THIRD BOOK: Short stories

So at the beginning of the eighties I started to feel all the more confident about my writing vocation; some day, in the near future, I would be a writer. Psycho-brothel (1983) and This is no cinema, baby (1985), two short story collections (with some poems loosely incorporated into the narrative of both) had a certain impact to the then anarchist youth movement in Greece, and to such an extent that the latter title became a familiar slogan that was posted on every wall in the Exarcheia district, the students' "Rive gauche" in Athens. I was reading the beatniks at the time. And some of the classic Greek writers, pre-modernists of the 19th century (Papadiamantis, Bizyinos, Roides, Mitsakis). And Joyce, of course, that goes without saying. Plus Bukowski.

These first three books constitute, in their peculiar way, a trilogy of experiments in content and style – in fact more in style, content didn't bother me much because, one way or another, it was meant to be committed to my socialist utopian positions. Style, narrative form, that was what I worked more intensely upon because I understood literature primarily as an art form. And I still do. (More about this trilogy, which I loosely call The A.M.'s 80's trilogy, you may read here.)

FIRST ''MAJOR'' literary ATTEMPT: The Portrait (1993)

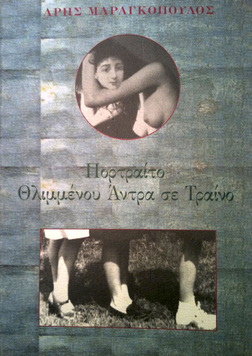

'Portrait of a Sad Young Man in the Train', the cover.

Jeune homme triste dans un train, (= Sad young man in the train) is the title of a well-known work by Marcel Duchamps (1887–1968) painted in 1911. This same title slightly modified (Portrait of a Sad young man in the train) I have borrowed for my second long scope novel (Greek title: Πορτραίτο Θλιμμένου Άντρα σε Τραίνο).

Marcel Duchamps 's conscientious choice to treat life as an objet d' art coincided with my ideals as an artist. This book was published in 1993 but had been planned a decade

earlier, that is in 1984. Working on this project for ten whole

years, that is between the age of 36 and 46, made me from

time to time feel really happy, that is artistically fulfilled – and consequently reassured for my ability to understand through the writing medium the

world (and share the acquired knowledge with other people). It was in this book that appeared for the first time the character of Benjamin Sanidopoulos, a newspaper man in his forties living as a poète maudit.

Published by a small publishing house, with minimal diffusion potential in the book market and by a writer unable to exploit professionally the usual canals of exchange and communication (crowded by detestable people in the book business and the media, poets, editors, reviewers, etc.), a writer who used to work in careful distance from the people of the métier, the book had a very short reading life. So, for a while, I actually turned into a really sad man. I decided to work on something quite different. Something I was thinking to do since my early twenties, when for the first time I had laid hands upon Joyce 's Ulysses.

Published by a small publishing house, with minimal diffusion potential in the book market and by a writer unable to exploit professionally the usual canals of exchange and communication (crowded by detestable people in the book business and the media, poets, editors, reviewers, etc.), a writer who used to work in careful distance from the people of the métier, the book had a very short reading life. So, for a while, I actually turned into a really sad man. I decided to work on something quite different. Something I was thinking to do since my early twenties, when for the first time I had laid hands upon Joyce 's Ulysses.

JOYCE, ME and minor consequences

Well, if you come to think of it there 's a small distance to cover between Marcel D. and James J. In fact my amateur practice in the arts plus the academic experience of the modernist movement I possessed until then made it easier for me to understand, and most of all, to enjoy Joyce. And there's more to it: for about 10 years, during the same time that I was working on the Portrait, I had been reading, almost everyday of my life, Ulysses, usually taking

lengthy notes, at the end of each day. So, when I made up my mind to

undertake a more serious journey to the Joycean Archipelago, my library

contained already a considerable pile of notes and an extensive

bibliography on the matter.

This critical reading culminated in the first version of a Companion Guide to Ulysses: 'Ulysses', A Guide to Seafarers (in Greek: 'Ulysses', Oδηγίες προς ναυτιλλομένους, Επιστρέφοντας στον 'Οδυσσέα' του Τζέιμς Τζόις) in 1995. Joyce exists as a distinctive chapter in my literary life. More about my relation to his work you may find in a separate menu. However my Joycean book had an unexpected effect on the peripheral Greek intelligentsia. People began discussing my 'daring' (plus illuminating) approach to the Joycean text, discussing extensively my modernist stand, 'discovering' me, getting accustomed to my somewhat uncommon entrance to the literary milieu. Of course nobody mentioned my other literary work, nobody seemed interested to read, discuss, criticize the novels and stories. As if they did not exist. Which means that they treated my work on Joyce as if it had been created in vitro. Life was disappointing once more for this man of letters, Mr. A.M. But at least he was acknowledged as a critic. Not a novelist, not a writer, a literary critic. So at this period, around 1997-8, he started a free-lance collaboration with almost all national newspapers: articles on theory of art, reviews of literary books, even political essays appeared on a regular basis in the literary supplements of the Press. CRITIC AND THEN: AUTHOR AGAIN Being a regular critic in the newspapers grants you a certain aura of power – especially if you are as I used to be, a very austere and demanding reviewer of literature whose critical stand could in no case be influenced by 'friendships', 'alliances' or 'pressures' imposed by the self appointed 'masters' of the literary milieu or by the 'bosses' of the book market. Keeping very carefully distances from that annoying influence and imposing a sui generis position in the Greek letters A.M. began to be established as a demanding critic and, at last, a writer as well. But alas! Revenge, oh! revenge and petit bourgeois conspiracy bound together (coming from those not favored, as they expected, by his reviews) helped understate his authorial status: most people from then on referred to him as a good but difficult author! His Joycean / modernist background served as the best credential to that provincial calumny! And he kept writing. And writing. And writing. Literature. As a result The Sanidopoulos Trilogy, which has been completed between the years 1998-2006, presented to all 'dissenters' a fresh, a more self-confident profile of the author, demanding more attention. However a real change in critical reception took place only after his third book, Obsession with Spring, received a considerable number of positive reviews. But for the Trilogy you should visit a separate page here. |

AUTHOR OF the new century

The first decade of the new century has proved very proliferating for A.M.'s book factory. In addition to the Sanidopoulos Trilogy (last volume completed) and in a period of less than ten years the author produced a good number of various books: two novellae, one important essay, a book of short stories, and very original illustrated books. This production draws certainly from earlier years work in progress and coincides with the author's professional involvement in the publishing business.

The first decade of the new century has proved very proliferating for A.M.'s book factory. In addition to the Sanidopoulos Trilogy (last volume completed) and in a period of less than ten years the author produced a good number of various books: two novellae, one important essay, a book of short stories, and very original illustrated books. This production draws certainly from earlier years work in progress and coincides with the author's professional involvement in the publishing business.